Before using zombies as a metaphor for the dehumanizing treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo, Slavoj Zizek drew attention to a significant but often overlooked characteristic of zombies [1992]:

The eyes of the undead are typically turned up so the irises are hidden and only white is shown (or sometimes the irises are even blotted out completely by the noxious fluid that animates the zombie). This blankness of expression emphasizes the lack of an inner fire, as well as an incongruence between what zombies once were and what they have become.

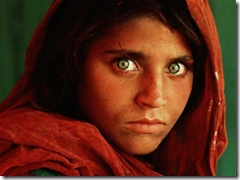

Contrast this with the eyes of the Afghan girl above, captured by a National Geographic photographer’s camera in 1985, which seem to overflow with the story of her life.

Zizek plays on this common association of the eyes with the soul to draw a connection between the empty eyes of the undead and the windows of an abandoned house. The origin of this perceived affinity between eyes and souls is difficult to track down, however. William Blake observed that “This life’s dim windows of the soul / Distorts the heavens from pole to pole.” This in turn appears to be a reference to an older English folk saying, The eyes are the windows of the soul or, alternatively, The eyes are the windows to the soul, which the OED traces back to the sixteenth century. Yet we also find a variation of this proverb in French, Les yeux sont le miroir de l’ame, which can loosely be translated as “The eyes are a reflection of the heart.” de.wikiquote.org turns up Das Auge ist ein Fenster in die Seele as a German proverb, but erroneously ascribes it to the Bible.

Rather than the Bible, the connection may lead back to ancient greek psychology. In the Timaeus, Plato propounds a theory of vision involving both an inner fire and an outer fire created by the Demiurge. Following Empedocles, Plato states that the inner fire lies behind the eyes, and in the act of perceiving emits rays that reach out, Superman-like, to touch the object being perceived. At the object, the rays carrying the inner fire co-mingle with the light around the thing perceived and return this mixed light to the eyes and to the perceptive soul.

In On Sense and the Sensible, Aristotle rejects his master’s notion of an inner fire, among other reasons because he finds it unnecessary. Rather than a fire going out and then coming back in, Aristotle proposes that light from the object simply enters the eye, as we believe today. He points out the mistaken notion that the visual organ is made of fire (natural science in the ancient world always revolved around the four elements) has its source in the bright lights one sees when one presses a finger against the eye. Centuries later, Isaac Newton describes a similar experiment he self-inflicted by pushing a stick against his own eye, to see what would happen.

Aristotle proposes that the eye, in particular the pupil, is made of water rather than fire, for it has this particular characteristic of water: it is transparent. Instead of serving as an active organ of attention, shooting out rays towards the world, the eye is a passive organ that receives impressions of color and magnitude which it passes to the soul, forming an impression of the sensible forms upon the soul as a signet ring forms an impression upon a piece of wax.

In On the Motion of Animals and On the Generation of Animals, Aristotle outlines a physical theory of pneuma, a fine substance which permeates the body and carries sense impressions to the heart, which is the organ of the sixth sense (an organ he earlier denied exists in On the Soul), or the common sense. This pneumatic theory was further developed by Aristotle’s disciples, then by the Stoics, and eventually made its way into Renaissance psychology.

In his 1984 study of Renaissance phantasmic pneuma, Eros and Magic, Ioan Couliano surveys the problem of pneumatic infection through the eyes. On the one hand, this takes the form of the evil eye, in which a diseased eye or an eye filled with malice can infect a person through the sensory organ and pneuma, thus taking over the sensus communis and causing a wasting away of the infected victim. On the other, it takes the form of romantic infatuation, in which the beloved’s image takes over the lover’s soul and, when the love is unrequited, causes a similar wasting away of the victim. This erotic phenomenon led the poet Giacomo da Lentino to ask, “How can it be that so large a woman has been able to penetate my eyes, which are so small, and then enter my heart and my brain?” Following the Platonic theory of ingneous optical rays, French poets identified this with fleches d’amour, an image which still persists in modern culture, though out of context, as Cupid’s arrows. In its proper context, we can better understand Leonardo da Vinci’s observation “that the eyes of virgins have the power to attract the love of men.”

— Eros and Magic in the Renaissance, tr. Margaret Cook

All the foregoing has assumed that the affinity between eyes and souls is a cultural artifact. An alternative case can be made that the cultural function of the eyes is actually a side-effect of how we see the world. Studies of the brain indicate that the interpretation of other people’s emotional states tend to concentrate on the eyes, and a great deal of our brain capacity is devoted to this particular task. The amygdala, a part of the brain connected to the visual cortex and responsible for regulating fear reactions, has been shown to respond more strongly to larger (fearful) eye whites than to smaller (happy) eye whites. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Arthur Arun, a New York psychiatrist, has performed experiments demonstrating that simply encouraging people to stare into each other’s eyes for a length of time can instill feelings of attraction.

The proverb the eyes are the windows to the soul may mask a physicalist truth, that the eyes are not a metaphor for the soul, but rather the soul is a metaphor for the eyes. In the eyes we see the essence of another person: their emotions which over time become a model of our expectations of how they will respond to us. The eyes are a touchstone allowing us to project thoughts and beliefs upon other people. We introspect to triangulate our beliefs, eye expressions, and emotions, and from this matrix try to determine if another person responds as we would, or as we would like. We look to the eyes to determine a person’s depth of emotion, and consequently their depth of spirit. And when those eyes are empty, there is no longer anything present to project upon or interpret.

— On the Generation of Animals, tr. Arthur Platt