VistaSpeechAPIDemo.zip – 45.7 Kb

VistaSpeechAPISource.zip – 405 Kb

Introduction

One of the coolest features to be introduced with Windows Vista is the new built in speech recognition facility. To be fair, it has been there in previous versions of Windows, but not in the useful form in which it is now available. Best of all, Microsoft provides a managed API with which developers can start digging into this rich technology. For a fuller explanation of the underlying technology, I highly recommend the Microsoft whitepaper. This tutorial will walk the user through building a common text pad application, which we will then trick out with a speech synthesizer and a speech recognizer using the .Net managed API wrapper for SAPI 5.3. By the end of this tutorial, you will have a working application that reads your text back to you, obeys your voice commands, and takes dictation. But first, a word of caution: this code will only work for Visual Studio 2005 installed on Windows Vista. It does not work on XP, even with .NET 3.0 installed.

Background

Because Windows Vista has only recently been released, there are, as of this writing, several extant problems relating to developing on the platform. The biggest hurdle is that there are known compatibility problems between Visual Studio and Vista. Visual Studio.NET 2003 is not supported on Vista, and there are currently no plans to resolve any compatibility issues there. Visual Studio 2005 is supported, but in order to get it working well, you will need to make sure you also install service pack 1 for Visual Studio 2005. After this, you will also need to install a beta update for Vista called, somewhat confusingly, “Visual Studio 2005 Service Pack 1 Update for Windows Vista Beta”. Even after doing all this, you will find that all the new cool assemblies that come with Vista, such as the System.Speech assembly, still do not show up in your Add References dialog in Visual Studio. If you want to have them show up, you will finally need to add a registry entry indicating where the Vista dll’s are to be found. Open the Vista registry UI by running regedit.exe in your Vista search bar. Add the following registry key HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\.NETFramework\AssemblyFolders\v3.0 Assemblies with this value: C:\\Program Files\\Reference Assemblies\\Microsoft\\Framework\\v3.0. (You can also install it under HKEY_CURRENT_USER, if you prefer.) Now, we are ready to start programming in Windows Vista.

Before working with the speech recognition and synthesis functionality, we need to prepare the ground with a decent text pad application to which we will add on our cool new toys. Since this does not involve Vista, you do not really have to follow through this step in order to learn the speech recognition API. If you already have a good base application, you can skip ahead to the next section, Speechpad, and use the code there to trick out your app. If you do not have a suitable application at hand, but also have no interest in walking through the construction of a text pad application, you can just unzip the source code linked above and pull out the included Textpad project. The source code contains two Visual Studio 2005 projects, the Textpad project, which is the base application for the SR functionality, and Speechpad, which includes the final code.

All the same, for those with the time to do so, I feel there is much to gain from building an application from the ground up. The best way to learn a new technology is to use it oneself and to get one’s hands dirty, as it were, since knowledge is always more than simply knowing that something is possible; it also involves knowing how to put that knowledge to work. We know by doing, or as Giambattista Vico put it, verum et factum convertuntur.

Textpad

Textpad is an MDI application containing two forms: a container, called Main.cs, and a child form, called TextDocument.cs. TextDocument.cs, in turn, contains a RichTextBox control.

Create a new project called Textpad. Add the “Main” and “TextDocument” forms to your project. Set the IsMdiContainer property of Main to true. Add a MainMenu control and an OpenFileDialog control (name it “openFileDialog1”) to Main. Set the Filter property of the OpenFileDialog to “Text Files | *.txt”, since we will only be working with text files in this project. Add a RichTextBox control to “TextDocument”, name it “richTextBox1”; set its Dock property to “Fill” and its Modifiers property to “Internal”.

Add a MenuItem control to MainMenu called “File” by clicking on the MainMenu control in Designer mode and typing “File” where the control prompts you to “type here”. Set the File item’s MergeType property to “MergeItems”. Add a second MenuItem called “Window“. Under the “File” menu item, add three more Items: “New“, “Open“, and “Exit“. Set the MergeOrder property of the “Exit” control to 2. When we start building the “TextDocument” form, these merge properties will allow us to insert menu items from child forms between “Open” and “Exit”.

Set the MDIList property of the Window menu item to true. This automatically allows it to keep track of your various child documents during runtime.

Next, we need some operations that will be triggered off by our menu commands. The NewMDIChild() function will create a new instance of the Document object that is also a child of the Main container. OpenFile() uses the OpenFileDialog control to retrieve the path to a text file selected by the user. OpenFile() uses a StreamReader to extract the text of the file (make sure you add a using declaration for System.IO at the top of your form). It then calls an overloaded version of NewMDIChild() that takes the file name and displays it as the current document name, and then injects the text from the source file into the RichTextBox control in the current Document object. The Exit() method closes our Main form. Add handlers for the File menu items (by double clicking on them) and then have each handler call the appropriate operation: NewMDIChild(), OpenFile(), or Exit(). That takes care of your Main form.

#region Main File Operations

private void NewMDIChild()

{

NewMDIChild(“Untitled”);

}

private void NewMDIChild(string filename)

{

TextDocument newMDIChild = new TextDocument();

newMDIChild.MdiParent = this;

newMDIChild.Text = filename;

newMDIChild.WindowState = FormWindowState.Maximized;

newMDIChild.Show();

}

private void OpenFile()

{

try

{

openFileDialog1.FileName = “”;

DialogResult dr = openFileDialog1.ShowDialog();

if (dr == DialogResult.Cancel)

{

return;

}

string fileName = openFileDialog1.FileName;

using (StreamReader sr = new StreamReader(fileName))

{

string text = sr.ReadToEnd();

NewMDIChild(fileName, text);

}

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

MessageBox.Show(ex.Message);

}

}

private void NewMDIChild(string filename, string text)

{

NewMDIChild(filename);

LoadTextToActiveDocument(text);

}

private void LoadTextToActiveDocument(string text)

{

TextDocument doc = (TextDocument)ActiveMdiChild;

doc.richTextBox1.Text = text;

}

private void Exit()

{

Dispose();

}

#endregion

To the TextDocument form, add a SaveFileDialog control, a MainMenu control, and a ContextMenuStrip control (set the ContextMenuStrip property of richTextBox1 to this new ContextMenuStrip). Set the SaveFileDialog’s defaultExt property to “txt” and its Filter property to “Text File | *.txt”. Add “Cut”, “Copy”, “Paste”, and “Delete” items to your ContextMenuStrip. Add a “File” menu item to your MainMenu, and then “Save“, Save As“, and “Close” menu items to the “File” menu item. Set the MergeType for “File” to “MergeItems”. Set the MergeType properties of “Save”, “Save As” and “Close” to “Add”, and their MergeOrder properties to 1. This creates a nice effect in which the File menu of the child MDI form merges with the parent File menu.

The following methods will be called by the handlers for each of these menu items: Save(), SaveAs(), CloseDocument(), Cut(), Copy(), Paste(), Delete(), and InsertText(). Please note that the last five methods are scoped as internal, so they can be called by the parent form. This will be particularly important as we move on to the Speechpad project.

#region Document File Operations

private void SaveAs(string fileName)

{

try

{

saveFileDialog1.FileName = fileName;

DialogResult dr = saveFileDialog1.ShowDialog();

if (dr == DialogResult.Cancel)

{

return;

}

string saveFileName = saveFileDialog1.FileName;

Save(saveFileName);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

MessageBox.Show(ex.Message);

}

}

private void SaveAs()

{

string fileName = this.Text;

SaveAs(fileName);

}

internal void Save()

{

string fileName = this.Text;

Save(fileName);

}

private void Save(string fileName)

{

string text = this.richTextBox1.Text;

Save(fileName, text);

}

private void Save(string fileName, string text)

{

try

{

using (StreamWriter sw = new StreamWriter(fileName, false))

{

sw.Write(text);

sw.Flush();

}

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

MessageBox.Show(ex.Message);

}

}

private void CloseDocument()

{

Dispose();

}

internal void Paste()

{

try

{

IDataObject data = Clipboard.GetDataObject();

if (data.GetDataPresent(DataFormats.Text))

{

InsertText(data.GetData(DataFormats.Text).ToString());

}

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

MessageBox.Show(ex.Message);

}

}

internal void InsertText(string text)

{

RichTextBox theBox = richTextBox1;

theBox.SelectedText = text;

}

internal void Copy()

{

try

{

RichTextBox theBox = richTextBox1;

Clipboard.Clear();

Clipboard.SetDataObject(theBox.SelectedText);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

MessageBox.Show(ex.Message);

}

}

internal void Cut()

{

Copy();

Delete();

}

internal void Delete()

{

richTextBox1.SelectedText = string.Empty;

}

#endregion

Once you hook up your menu item event handlers to the methods listed above, you should have a rather nice text pad application. With our base prepared, we are now in a position to start building some SR features.

Speechpad

Add a reference to the System.Speech assembly to your project. You should be able to find it in C:\Program Files\Reference Assemblies\Microsoft\Framework\v3.0\. Add using declarations for System.Speech, System.Speech.Recognition, and System.Speech.Synthesis to your Main form. The top of your Main.cs file should now look something like this:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.ComponentModel;

using System.Data;

using System.Drawing;

using System.Text;

using System.Windows.Forms;

using System.IO;

using System.Speech;

using System.Speech.Synthesis;

using System.Speech.Recognition;

In design view, add two new menu item to the main menu in your Main form labeled “Select Voice” and “Speech“. For easy reference, name the first item selectVoiceMenuItem. We will use the “Select Voice” menu to programmatically list the synthetic voices that are available for reading Speechpad documents. To programmatically list out all the synthetic voices, use the following three methods found in the code sample below. LoadSelectVoiceMenu() loops through all voices that are installed on the operating system and creates a new menu item for each. VoiceMenuItem_Click() is simply a handler that passes the click event on to the SelectVoice() method. SelectVoice() handles the toggling of the voices we have added to the “Select Voice” menu. Whenever a voice is selected, all others are deselected. If all voices are deselected, then we default to the first one.

Now that we have gotten this far, I should mention that all this trouble is a little silly if there is only one synthetic voice available, as there is when you first install Vista. Her name is Microsoft Anna, by the way. If you have Vista Ultimate or Vista Enterprise, you can use the Vista Updater to download an additional voice, named Microsoft Lila, which is contained in the Simple Chinese MUI. She has a bit of an accent, but I am coming to find it rather charming. If you don’t have one of the high-end flavors of Vista, however, you might consider leaving the voice selection code out of your project.

private void LoadSelectVoiceMenu()

{

foreach (InstalledVoice voice in synthesizer.GetInstalledVoices())

{

MenuItem voiceMenuItem = new MenuItem(voice.VoiceInfo.Name);

voiceMenuItem.RadioCheck = true;

voiceMenuItem.Click += new EventHandler(voiceMenuItem_Click);

this.selectVoiceMenuItem.MenuItems.Add(voiceMenuItem);

}

if (this.selectVoiceMenuItem.MenuItems.Count > 0)

{

this.selectVoiceMenuItem.MenuItems[0].Checked = true;

selectedVoice = this.selectVoiceMenuItem.MenuItems[0].Text;

}

}

private void voiceMenuItem_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

SelectVoice(sender);

}

private void SelectVoice(object sender)

{

MenuItem mi = sender as MenuItem;

if (mi != null)

{

//toggle checked value

mi.Checked = !mi.Checked;

if (mi.Checked)

{

//set selectedVoice variable

selectedVoice = mi.Text;

//clear all other checked items

foreach (MenuItem voiceMi in this.selectVoiceMenuItem.MenuItems)

{

if (!voiceMi.Equals(mi))

{

voiceMi.Checked = false;

}

}

}

else

{

//if deselecting, make first value checked,

//so there is always a default value

this.selectVoiceMenuItem.MenuItems[0].Checked = true;

}

}

}

We have not declared the selectedVoice class level variable yet (your Intellisense may have complained about it), so the next step is to do just that. While we are at it, we will also declare a private instance of the System.Speech.Synthesis.SpeechSynthesizer class and initialize it, along with a call to the LoadSelectVoiceMenu() method from above, in your constructor:

#region Local Members

private SpeechSynthesizer synthesizer = null;

private string selectedVoice = string.Empty;

#endregion

public Main()

{

InitializeComponent();

synthesizer = new SpeechSynthesizer();

LoadSelectVoiceMenu();

}

To allow the user to utilize the speech synthesizer, we will add two new menu items under the “Speech” menu labeled “Read Selected Text” and “Read Document“. In truth, there isn’t really much to using the Vista speech synthesizer. All we do is pass a text string to our local SpeechSynthesizer object and let the operating system do the rest. Hook up event handlers for the click events of these two menu items to the following methods and you will be up and running with an SR enabled application:

#region Speech Synthesizer Commands

private void ReadSelectedText()

{

TextDocument doc = ActiveMdiChild as TextDocument;

if (doc != null)

{

RichTextBox textBox = doc.richTextBox1;

if (textBox != null)

{

string speakText = textBox.SelectedText;

ReadAloud(speakText);

}

}

}

private void ReadDocument()

{

TextDocument doc = ActiveMdiChild as TextDocument;

if (doc != null)

{

RichTextBox textBox = doc.richTextBox1;

if (textBox != null)

{

string speakText = textBox.Text;

ReadAloud(speakText);

}

}

}

private void ReadAloud(string speakText)

{

try

{

SetVoice();

synthesizer.Speak(speakText);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

MessageBox.Show(ex.Message);

}

}

private void SetVoice()

{

try

{

synthesizer.SelectVoice(selectedVoice);

}

catch (Exception)

{

MessageBox.Show(selectedVoice + “\” is not available.);

}

}

#endregion

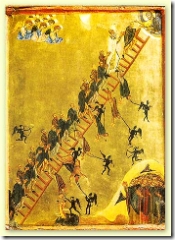

Whereas Kircher’s search for transcendence requires great learning, the icon to the right, of the

Whereas Kircher’s search for transcendence requires great learning, the icon to the right, of the