One of the fights that I thought we had put behind us is over the question ‘which interface is better?’ For instance, this question the was frequently brought up in comparisons of the mouse to the keyboard, its putative precursor. The same disputes came along again with the rise of natural user interfaces (NUI) when people began to ask if touch would put the mouse out of business. Always the answer has been no. Instead, we use all of these input modes side-by-side.

As Bill Buxton famously said, every technology is the best at something and the worst at something else. We use the interface best adapted to the goal we have in mind. In the case of data entry, the keyboard has always been the best tool. For password entry, on the other hand, while we have many options, including face and speech recognition, it is remarkable how often we turn to the standard keyboard or keypad.

Yet I’ve found myself sucked into arguments about which is the best interaction model, the HoloLens v1’s simple gestures, the Magic Leap One’s magnetic 6DOF controller, or the HoloLens v2’s direct manipulation (albeit w/o haptics) with hand tracking.

Ideally we would use them all. A controller can’t be beat for precision control. Direct hand manipulation is intuitive and fun. To each of these I can add a blue tooth XBox controller for additional freedom. And the best replacement for a keyboard turns out to be a keyboard (this is known as the Qwerty’s universal constant).

It was over two years ago at the Magic Leap conference that James Powderly, a spatial computing UX guru, set us on the direction of figuring out ways to use multiple input modalities at the same time. Instead of thinking of the XOR scenario (this or that but not both) we started considering the AND scenario for inputs. We had a project at the time, VIM – an architectural visualization and data reporting tool for spatial computing –, to try it out with. Our main rule in doing this was that it couldn’t be forced. We wanted to find a natural way to do multi-modal that made sense and hopefully would also be intuitive.

We found a good opportunity as we attempted to refine the ability to move building models around on a table-top. This is a fairly universal UX issue in spatial computing, which made it even more fascinating to us. There are usually a combination of transformations that can be performed on a 3D object at the same time for ease of interaction: translation (moving from position x1 to position x2), scaling the size of the object, and rotating the object. A common solution is to make each of these a different interaction mode triggered by clicking on a virtual button or something.

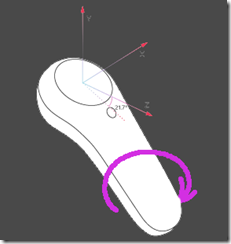

But we went a different way. As you move a model in space by pointing the Magic Leap controller in different directions like a laser pointer with the building hanging off the end, you can also push it away by pressing on the top of the touch pad or rotate it by spinning your thumb around the edge of the touch pad.

This works great for accomplishing many tasks at once. A side effect, though, is that while users rotated a 3D building with their thumbs, they also had a tendency to shake the controller wildly so that it seemed to get tossed around the room. It took an amazing amount of dexterity and practice to rotate the model while keeping it in one spot.

To fix this, we added a hand gesture to hold the model in place while the user rotated it. We called this the “halt” gesture because it just required the user to put up their off hand with the palm facing out. (Luke Hamilton, our Head of Design, also called this the “stop in the name of love” gesture.)

But we were on a gesture inventing roll and didn’t want to stop. We started thinking about how the keyboard is more accurate and faster than a mouse in data entry scenarios, while the mouse is much more accurate than a game controller or hand tracking for pointing and selecting.

We had a similar situation here where the rotation gesture on the Magic Leap controller was intended to make it easy to spin the model in a 360 degree circle, but consequently was not so good for very slight rotations (for instance the kind of rotation needed to correctly orient a life-size digital twin of a building).

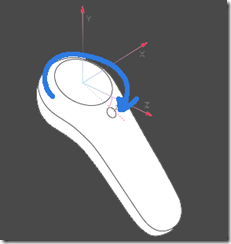

We got on the phone with Brian Schwab and Jay Juneau at Magic Leap and they suggested that we try to use the controller in a different way. Rather than simply using the thumb pad, we could instead rotate the controller on its Z-axis (a bit like a screwdriver) as an alternative rotational gesture. Which is what we did, making this a secondary rotation method for fine-tuning.

And of course we combined the “halt / stop in the name of love” gesture with this “screwdrive” gesture, too. Because we could but more importantly because it made sense and most importantly because it allows the user to accomplish her goals with the least amount of friction.