Crazyfinger makes an interesting comment on Jeff Jarvis’s blog.

Deadwood. The blogosphere of today feels like that town, with its own version of Swearengens, E. B. Farnums…

There is a lot of background to this, worth unpacking; it can all be distilled, however, to the observation that people are sometimes mean on the internet.

The long version goes something like this. Kathy Sierra, who is an admired web design guru, Web 2.0 advocate, and co-author of the immensely popular Head First series of technical books, has a blog. And recently people started making obnoxious comments on her blog, obnoxious comments on other blogs about her, works of Photoshop clipping involving her, and finally death threats. She is now considering getting out of the blogosphere altogether, a dramatic instance of Gresham’s law at work. In the meantime, however, it turns out she has some notable friends who are now trying to use their influence to do something about the netnasties. Tim O’Reilly, who runs a successful technical press and also helped coin the term Web 2.0, proposes a blogger code of conduct to which bloggers can sign on as a mark of their bona fides.

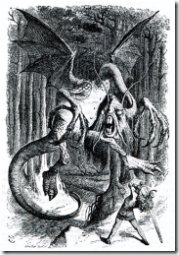

In other milieus, this mild suggestion of self-regulation would seem perfectly reasonable, but the internet is not just any milieu. It has mythic origins as an unregulated medium for the transmission of ideas and great hopes — democratic ideals, anarchic utopias, freedom of speech, freedom of expression — are tied to it. The wildness of the internet contributes to its appeal. Like the American frontier, it is a terrain where anyone can re-create themselves, and build a new culture in which they can happily dwell.

This conjoining of freedom, the Internet, the blogosphere, Web 2.0, and the Open Source movement was at one time promoted by the same people who are finding problems with it now. In a 2006 commencement speech at UC Berkeley’s School of Information, Tim O’Reilly said:

The internet has enormous power to increase our freedom. It also has enormous power to limit our freedom, to track our every move and monitor our every conversation. We must make sure that we don’t trade off freedom for convenience or security.

In his own explication of what his neologism Web 2.0 meant, O’Reilly wrote:

If an essential part of Web 2.0 is harnessing collective intelligence, turning the web into a kind of global brain, the blogosphere is the equivalent of constant mental chatter in the forebrain, the voice we hear in all of our heads. It may not reflect the deep structure of the brain, which is often unconscious, but is instead the equivalent of conscious thought. And as a reflection of conscious thought and attention, the blogosphere has begun to have a powerful effect.

Kathy Sierra has been more consistent in her view of the openness of the Internet. In 2005 she discussed the enforcement of “be-nice” rules on a forum she started.

Enforcing a “be nice” rule is a big commitment and a risk. People complain about the policy all the time, tossing out “censorship” and “no free speech” for starters. We see this as a metaphor mismatch. We view javaranch as a great big dinner party at the ranch, where everyone there is a guest. The ones who complain about censorship believe it is a public space, and that all opinions should be allowed. In fact, nearly all opinions are allowed on javaranch. It’s usually not about what you say there, it’s how you say it.

And this isn’t about being politically correct, either. It’s a judgement call by the moderators, of course. It’s fuzzy trying to decide exactly what constitutes “not nice”, and it’s determined subjectively by the culture of the ranch.

At the same time, it was also she who pointed out, quite accurately, this principle of the Internet:

If we want our users (members, guests, students, potential customers, kids, co-workers, etc.) to pay attention, we have to be provocative. We can moan all we want about how the responsible person should pay attention to what’s important rather than what’s compelling. But it’s not about responsibility or maturity. It’s not even about interest.

…

Provocation is in the eye of the provoked, obviously, so there’s no clear formula. But there’s plenty we can try, depending on the circumstances….

These notions of the Internet age as herald to a new form of social interaction even permeates seemingly unrelated movements like the Agile Methodology for software development, which promotes:

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Responding to change over following a plan

Even the Open Source movement, which promotes a particular way of distributing software, includes these interesting stipulations in the license they promulgate:

By open, they truly mean open. Given this emphasis on ideals of individuality, freedom, and equality in Internet culture, it can be seen why any suggestion that it might be in everyone’s interest to curtail any of these is seen as anathema. It also explains the strange bind those working on O’Reilly’s proposed blogger’s code of conduct find themselves in. Once it was agreed upon that some sort of action should be taken to deal with the netnasties, it was discovered that nothing could really be done without enforcement, and no one wants enforcement since it is a form of coercion. Consequently, the code of conduct has turned out to be a document that offends half of the Internet by suggesting mild coercion in the first place, and then draws the dirision of the other half by having no teeth. The draft code of conduct is currently in a state of flux, and may change radically over the next several weeks. At one point, however, it included an article that stated that bloggers don’t take themselves seriously. The intent of this was somewhat lost to me, but the irony was not. Bloggers don’t take themselves seriously, and yet they feel they need a code of conduct to explicate what they believe in, including the tenet that they don’t take themselves seriously.

As it is shaping up, though, the code of conduct ressembles to a remarkable degree the bylaws of various community forums across the Internet. What separates forums from blogs is, primarily, that forums are composed of people who consent to obey the oversight of moderators as a mechanism for regulating discussions. Blogs, on the other hand, are visible and generally accessible to everyone. Forums usually have mechanisms in place to eject members who repeatedly behave badly. The Internet has no such mechanism. Finally, forums usually only provide one with an audience of a hundred to a thousand people. Blogs offer a potential audience of hundreds of millions of people.

It is likely for this last reason that many people have turned to blogs, rather than forums, as their main outlet for Internet discourse. If gold was the main currency of the Old West, attention is the main currency of the new frontier — or, as advertisers like to call it, eyeballs. The public life of many people on the Internet involves acquiring eyeballs, which can then be converted to real money if one chooses to advertise on one’s site, or else may simply be used as a mode of social promotion. Returning to moderated forums is akin to returning to the towns back East where laws were more stringent, and safety more assured, but opportunities for advancement and transformation were limited. The blogosphere holds out the promise that anyone can be famous if they turn the right phrase, capture the right attention, come up with the next big idea.

For these very reasons, however, the rules of a community cannot be enforced where no laws exist. How then does justice get enforced on the digital frontier?

As Crazyfinger (who has an interesting blog of his own about Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments) suggests, an analogy can be drawn between the TV drama Deadwood and the current state of the Internet. Had Deadwood survived another season, we might even have received a definitive answer, but as it is, we only have suggestions.

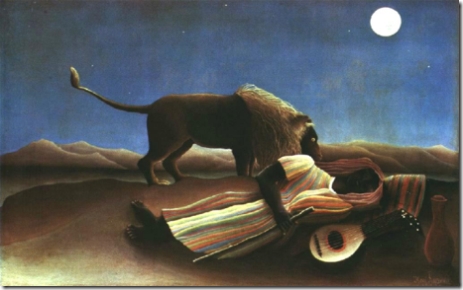

Deadwood, in the show of the same name, is a gold town in South Dakota marching slowly toward incorporation and civilization. Alma Garret (a proxy for Kathy Sierra) has accidentally struck it rich when her lot is discovered to contain one of the richest gold veins in the region. As a consequent, she is a victim of unscrupulous persons anxious to take hold of her, ermm, eyeballs. Having neither reputation to lose nor character to restrain them, they act provacatively in their efforts to raise their own social status.

Throughout the series, three main ways are provided to afford Alma Garret the protection of civilization she requires, in a place without civilization. The first is Wild Bill Hickock, who through the authority granted him by his reputation, is able to coerce people to behave appropriately. This is analogous to the the attempt by Kathy Sierra’s friend Tim O’Reilly, as well as others, to use their reputations to shame people into agreeing to some sort of blogging standards. Sadly, the attempt is also analogous to the letter written by the town fathers in Season Three in the local paper to turn sentiment against George Hearst, who has designs on Alma’s gold. Wild Bill, of course, is shot at the end of Season One. Best character on TV ever. Nuff said.

Alma Garret’s second line of defense is Sheriff Seth Bullock. Bullock is of heroic proportions. Through the exercise of precise and barely restrained violence, Bullock is able to herd and intimidate those who would upset the peace of Deadwood. Bullock is the equivalent of the sort of hero we occassionally encounter in forums and message boards, who through wit, knowledge, and force of character is able both to inspire people to behave better as well as punish with an acid tongue those who do not. Alas, on the Internet, there are too few of these, and the few there are tend to retreat into their own preoccupations over time. A case again, perhaps, of Gresham’s Law: bad money drives good money out of circulation.

The last option Alma Garret has at her disposal is to accede to the wishes of the villainous and violent George Hearst on the best terms she is able. This is what Alma Garret does at the end of Season Three, rather than force a confrontation that would likely see many of the main characters killed off. This, as far as I can see, is the only way to bring civilization to the blogosphere, and it is an unhappy turn. Civilization, once we accept that there will always be netnasties, is only possible when we turn a monopoly of coercive power over to a single entity. If, as O’Reilly, Sierra and others have argued, it is necessary to make the blogosphere and the Internet, by extension, obey the rules of a community forum, then something like this must occur. The most likely way for this to happen is if one of the main social networking sites joins forces with one of the major blogging hosts, such as Typepad or LiveJournal, and compels everyone who wants to blog to sign on to their service, following the other principle of the Internet that growth engenders growth. Having acquired a majority share of the blogosphere, such a monopolistic regime can then enforce community rules such as the ones Tim O’Reilly is attempted to formulate. This entails the victory of Hearst and of civilazation, and the closing of the frontier.

And, I think, it is also the moral of Deadwood, if there is a moral to be found. The frontier gives us heroes, but it also engenders monsters. The idealized vision of the frontier must at some point be confronted with the ugliness it foments; a place of greed, corruption, mysogeny, pornography and guys who say “cocksucker”. If we can’t find it in ourselves to embrace the ugliness along with the heroism of the frontier, then we must make the great compromise and bear the yoke which assures civility, and which, Rousseau promises, is only a light yoke, after all.