This past weekend a neighbor invited our entire subdivision to celebrate an Indian holiday called Diwali with them – The Festival of Lights. Like many traditions that immigrant families carry to the New World in their luggage, it had become an amalgamation of old and new. The hosts and other Indians from the neighborhood wore traditional South-East Asian formalwear. I was painfully underdressed in an old oxford, chinos and flip-flops. Others came in the formalwear of their native countries. Some just put on jackets and ties. We organized this Diwali as a pot-luck and had an interesting mix of biryanis, spaghetti, enchiladas, pancakes with syrup, borscht, tomato korma, Vietnamese spring rolls and puri.

The most important part of the celebration was the lighting of fireworks. For about two solid hour, children ran through a smoky cul-de-sac waving sparklers while firecrackers went off around them. Towards the end of this celebration, one of our hosts pulled out her iPhone in order to Facetime with her father in India and show him the children playing in the background just as they would have back home, forming a line of continuity between continents using a 1500 year old ritual and an international cellular system. Diwali is called the Festival of Lights, according to Wikipedia, because it celebrates the spiritual victory of light over darkness and ignorance.

When I got home I did some quick calculations. In order to get to that Apple moment our host had with her father – we no longer have Hallmark moments but only Apple moments today – took approximately seven years. This is the amount of time it takes for a technology to seem fantastic and impractical – because we don’t believe it can be done and can’t imagine how we would use it in everyday life if it was – to having it be unexceptional.

_thumb.jpg)

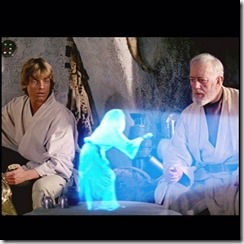

Video conferencing has been a staple of science fiction for ages, from 2001: A Space Odyssey to Star Trek. It was only in 2010, however, that Apple announced the FaceTime app making it generally available to anyone who could afford an iPhone. I’m basing the seven years from fantasy to facticity, though, on length of time since the initial release of the iPhone in 2007.

Magic Leap, the digital reality technology that has just received half a billion dollars of funding from companies like Google, is important because it points the way to what can happen in the next seven years. I will paint a picture for you of what a world with this kind of digital reality technology will look like and it’s perfectly okay if you feel it is too out there. In fact, if you end up thinking what I’m describing is plausible, then I haven’t done a good enough job of portraying that future.

Magic Leap is creating a wearable product which may or may not be called Dragonstone glasses and which may or may not be a combination of light field technology – like that used in the Lytro camera – and depth detection – like the Kinect sensor. They are very secretive about what they are doing exactly. When Leap Magic CEO Rony Abovitz talks about his product, however, he uses code to indicate what it is and what it isn’t.

In an interview with David Lidsky, Abovitz let slip that Dragonstone is “not holography, it’s not stereoscopic 3-D. You don’t need a giant robot to hold it over your head, you don’t need to be at home to use it. It’s not made from off-the-shelf parts. It’s not a cellphone in a View-Master.” At first reading, this seems like a quick swipe at Oculus Rift, the non-mobile, stereoscopic virtual reality solution built from consumer parts by Oculus VR and, secondarily, Samsung Gear VR, the mobile add-on to Samsung’s Galaxy Note 4 that turns it into a virtual reality device with stereoscopic audio. Dig a little deeper, however, and it’s apparent that his grand sweep of dismissal takes in a long list of digital reality plays over the years.

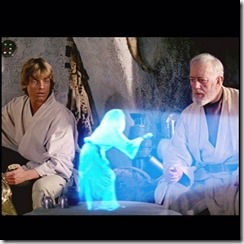

Let’s start with holography. Actually, let’s start with a very specific hologram.

The 1977 holographic chess game from Star Wars is the precursor to both virtual and augmented reality as we think of them – for convenience, I am including them all under the “digital reality” rubric. No child saw this and didn’t want it. From George Lucas imaginative leap, we already see an essential aspect of the digital experience we crave that differentiates it from the actual technology we have. Actual holography involves a frame that we view the virtual image through. In Lucas’s vision, however, the holograms take up space and have a location.

What’s intriguing about the Star Wars scene is that as a piece of film magic, the technology behind the chess game wasn’t particularly innovative. It’s pretty much just the same claymation techniques Ray Harryhausen and others had been using since the 50’s and involves superimposing a animated scene over a live scene. The difference comes in how George Lucas incorporates it into the story. Whereas all the earlier films that mixed live and animated sequences sought to create the illusion that the monsters were real, in the battle chess scene, it is clear that they are not – for instance because they are semi-transparent. Because the elements of the chess game are explicitly not real within the movie narrative – unlike Wookies, Hutts, and Ton-tons – they are suddenly much more interesting. They are something we can potentially recreate.

The difference between virtual reality and augmented reality is similarly one of context. Which is which depends on how we, as the observer, are related to the digital experience. In the case of augmented reality, the context is the real world into which digital objects are inserted. An example of this occurs in Empire Strikes Back [1980], where the binoculars on Hoth provide additional information presented as an overlay on the real world.

The popular conception of virtual reality, as opposed to the technical accomplishment, probably dates to the publication of William Gibson’s Neuromancer in 1984. Gibson’s “cyberspace” is a fully digital immersive world. Unlike augmented reality where the context is our reality, in cyberspace the context is a digital space into which we, as observers and participants, are superimposed.

To schematize the difference, in augmented reality, reality is the background and digital content is in the foreground; in virtual reality, the background that we perceive is digital while the foreground is a combination of digital and actual objects. I find this to be a clean way of distinguishing the two and preferable to the tendency to distinguish them based on different degrees of immersion. To the extent that contemporary VR is built around improving the video game experience, we see that POV games have, as a goal, to create increasingly realistic world – but what is more realistic than the real world. On the other side, augmented reality, when done right, have the potential to be incredibly immersive.

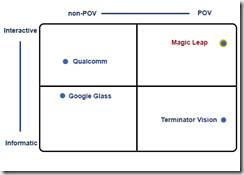

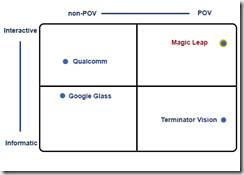

We can subdivide augmented reality even further. We’ll actually need to in order to elucidate why AR in Magic Leap is different from AR in Google Glass. Overlaying digital content on top of reality can take several forms and tends to fall along two axes. An AR experience is either POV or non-POV. It can also be either informational or interactive.

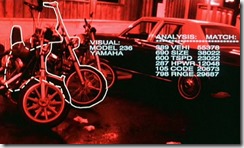

Augmented Reality in the POV-Informatics quadrant is often called Terminator Vision after the 1984 sci-fi Austrian body-builder augmented film. I’m not sure why a computer, the Terminator, would need a display to present data to itself, but in terms of the narrative it does wonders for the audience. It gives a completely false sense of what it must be like to think like a computer.

Experiences in the non-POV-Informatics quadrant are typically called Heads-Up-Displays or HUD. They have their source in military applications but are probably best known from first-person-shooters where the view-point is tied to objects like windshields or gun-sights rather than to the point-of-view of the player. They also don’t take up the entire view and consequently we can look away from them – unlike Terminator Vision. Google Glass is actually an example of a HUD – though it is sometimes mistaken for TV — since the display only fills up the right corner of the visual field.

Non-POV interactive can be either magic mirror experiences or hand-held games and advertisements involving fiducials. This is a common way of creating augmented reality experiences for the iPad and smartphones. The device camera is pointed toward a fiducial, such as a picture in a catalog, and a 3-D model is layered over the video returned by the camera. Interestingly Qualcomm, one of the backers in Magic Leaps recent round of funding, is also a leader in developing tools for this type of AR experience.

POV interactive, the final quadrant, is where Magic Leap falls. I don’t need to describe it because its exemplar is the sort of experience that Rony Abovitz says Dragonstone is not – the hologram from Star Wars. The difference is that where Abovitz is referring to the sort of holography we can do in actual reality, Magic Leap’s technology is the kind of holography that, so far, we have only been able to do in the movies.

If you examine the two images I’ve included from Star Wars IV, you’ll notice that the holograms are seen not from a single point of view but from multiple points of view. This is a feature of persistent augmented reality. The digital AR objects virtually exist in a real-world location and exist that way for multiple people. Even though Luke and Ben have different photons shooting at their eyes displaying the image of Leia from different perspectives, they are nevertheless looking at the same virtual Princess.

This kind of persistence, and the sort of additional technology required to make it work, helps to explain part of the reason Google is interested in it. Google, as we know, already has its own augmented reality play. Where Google brings something new to a POV interactive AR experience is in its expertise in geolocation, without which persistent AR entities would be much harder to create.

This sort of AR experience does not necessarily imply the use of glasses. We don’t know what sort of pseudo-technology is used the the Star Wars universe, but there are indications that it is some sort of projection. In Vernor Vinge’s sci-fi novel Rainbow’s End [2006], persistent augmented reality is projected on microscopic filaments that people experience without wearables.

Because Magic Leap is creating the experience inside a wearable close-range display, i.e. glasses, additional tricks are required. In addition to geolocation – which is only a guess at this point – it will also require some sort of depth sensor to determine if real-world objects are located between the viewer and the object’s location. If there is, then the occlusion of the virtual entity has to be simulated in the visualization – basically, a chunk has to be cut out of the image.

If I have described the Magic Leap technology correctly – and there’s a good chance I have not given the secretiveness around it – then what we are looking at seven years out is a world in which everything we see is constantly being photoshopped in real-time. At a basic level, this fulfills the Magic Leap promise to re-enchant the world with digital entities and also makes sense of their promotional materials.

There are also some interesting side-effects. For one, an augmented world would effectively turn everything and everyone into a potential billboard. Given Google’s participation, this seems even likely. As with the web, advertisements will pay for the content that populates an augmented reality world. Like the web and mobile devices, the same geolocation that makes targeted content possible may also be used to track our behavior.

There are additional social consequences. Many strange aspects of online behavior may make its way into our world. Pseudo-anonymity, which can encourage bad behavior in good people, can become a larger aspect of our world. Instead of appearing as themselves, people may prefer enhanced versions of themselves or even avatars.

In seven years, it may become normal to sit across a conference table from a giant rabbit and Master Chief discussing business strategies. Constant self-reinvention, which is a hallmark of the online experience, may become even more prevalent. In turn, reputation systems may also become more common as a way to curb the problems associated with anonymity. Liking someone I pass in the street may become much more literal.

There is also, however, the cool stuff. Technology, despite all the frequent articles to the contrary, has the power to bring people together. Imagine one day being able to share an indigenous festival with loved ones who live thousands of miles away. My eleven year-old daughter has grown up with friends from around the world whom she has met online. Technology allows her not only to chat with them with texts, but also to speak with them while she is performing chores or walking around the house. Yet she has never met any of them. In seven years, we may live in a world where physical distance no longer implies emotional distance and where sitting around chatting face-to-face with someone you have never actually met face-to-face does not seem at all strange.

For me, Magic Leap points to a future where physical limitations are no longer limitations in reality.

_thumb.jpg)

Whereas Kircher’s search for transcendence requires great learning, the icon to the right, of the

Whereas Kircher’s search for transcendence requires great learning, the icon to the right, of the