The latest Atlantic contains an article by Brian Christian on the annual Turing Test held in Brighton, England. In order to pass the Turing Test (also known as the Loebner Prize) a computer program must be able to fool 30 percent of the people it interacts with that it is human. In 2008, one program missed this goal by only one vote.

In the article, Christian quotes Douglas Hofstadter, the author of Godel, Escher, Bach, on the problem of ‘The Sentence.’ The Sentence is the perennial attempt to frame the all-important definition “The human being is the only animal that …” We once thought this sentence could be completed with uses language, uses tools, does mathematics, or plays chess, only to be confounded each time by further discoveries about the natural and mechanical world.

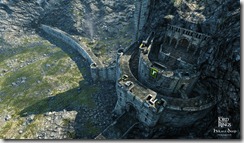

‘Sometimes it seems,’ says Douglas Hofstadter […] ‘as though each new step towards AI, rather than producing something which everyone agrees is real intelligence, merely reveals what real intelligence is not.’ While at first this seems a consoling position – one that keeps our unique claim to thought intact – it does bear the uncomfortable appearance of a gradual retreat, like a medieval army withdrawing from the castle to the keep. But the retreat can’t continue indefinitely. Consider: if everything that we thought hinged on thinking turns out to not involve it, then … what is thinking? It would seem to reduce to either an epiphenomenon – a kind of exhaust thrown off by the brain – or, worse, an illusion. Where is the keep of our selfhood? [emphasis mine]

I have always been a fan of footnotes. In complex academic works, it is usually the footnotes that contain the most fascinating insights. They are, in a sense, the epiphenomena of the academic world.

Stephen H. Voss has a fine translation of Descartes’s The Passions of the Soul, a work Descartes wrote for Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia years after separating the mind and the body in his Meditations on First Philosophy. What comes out in this later work – and to which attention is drawn in Voss’s footnotes — is that the line between mind and body is not a geographical division like that between countries, but rather a kinesthetic separation between the inside and the outside. In The Passions, Descartes even begins talking about the inner soul and the interior of the soul, further subdividing the line between self and world.

Concerning this, Voss writes in footnote 78:

Since the soul has no parts […], it is hard to see how to distinguish theoretically the interieur, let alone le plus interieur, of the soul from the rest of it. As we intimated in note 27* in Part I, it is perhaps more reasonable to see such passages as signs of Descartes’s genuinely neo-Stoic attitude toward the world. We have seen his focus successively narrow in this work: the body, the pineal gland, the soul, and now its ‘interior.’ A similar itinerary can be traced in the First Meditation: objects that are very small or far away, familiar nearby objects, the body and its senses, the soul and its reason. And so can one more: examining ‘the great book of the world’ on military travels through several countries; Amsterdam, Leyden, and the isolated village of Egmond; and finally the palace in Stockholm. What walled fastness can ever provide security? [emphasis mine]

I’ve always wondered if this kinesthetic problem of interiors and exteriors is related to the solution of using metalanguages to avoid problems of self-referentiality in logic. In particular, I’m thinking of Douglas Hofstadter’s chapter in Godel, Escher, Bach describing Russell and Whitehead’s Principia Matematica, called “Banishing Strange Loops”:

Russell and Whitehead did subscribe to this view [that self-reference is the root of all evil in logic], and accordingly, Principia Mathematica was a mammoth exercise in exorcising Strange Loops from logic, set theory, and number theory. The idea of their system was basically this. A set of the lowest ‘type’ could contain only ‘objects’ as members – not sets. A set of the next type up could only contain objects, or sets of the lowest type. In general, a set of a given type could only contain sets of lower type, or objects. Every set would belong to a specific type. Clearly, no set could contain itself because it would have to belong to a type higher than its own type […] To all appearances, then, this theory of types, which we might also call the ‘theory of the abolition of Strange Loops’, successfully rids set theory of its paradoxes, but only at the cost of introducing an artificial-seeming hierarchy, and of disallowing the formation of certain kinds of sets…

This connection I am (less-than-tentatively) proposing, of course, only works if interior and exterior can be mapped to the notions of higher and lower level languages. This is, however, how we typically think of the emergent self in evolutionary biology. The highest part of the mind — the most selfish bit – is also the last to have developed in time, while the lizard brain, which the higher functions always seek to constrain, is also considered the part that is least ourselves – it is a mechanical, biological process, and when that lizard brain is in control, we are out of control.

*footnote 27: A pervasive Cartesian conviction is that what is far away can deceive, while what is close at hand can give security. That is true not only of epistemic security (in addition to the present passage, see Meditations 1 and 3: AT VII, 18 and 37: CSM II, 12-13 and 27; and a. 1 above), but also of emotional security (see Discourse, Part 3: AT VI, 25-27: CSM I, 123-124; and aa 147-148 below).