There has been a recent spate of posts about authority in the world of software development, with some prominent software bloggers denying that they are authorities. They prefer to be thought of as intense amateurs.

I worked backwards to this problematic of authority starting with Jesse Liberty. Liberty writes reference books on C# and ASP.NET, so he must be an authority, right? And if he’s not an authority, why should I read his books? This led to Scott Hanselman, to Alastair Rankine and finally to Jeff Atwood at CodingHorror.com.

The story, so far, goes like this. Alastair Rankine posts that Jeff Atwood has jumped the shark on his blog by setting himself up as some sort of authority. Atwood denies that he is any sort of authority, and tries to cling to his amateur status like a Soviet-era Olympic poll vaulter. Scott Hanselman chimes in to insist that he is also merely an amateur, and Jesse Liberty (who is currently repackaging himself from being a C# guru to a Silverlight guru) does an h/t to Hanselman’s post. Hanselman also channels Martin Fowler, saying that he is sure Fowler would also claim amateur status.

Why all this suspicion of authority?

The plot thickens, since Jeff Atwood’s apologia, upon being accused by Rankine of acting like an authority, is that indeed he is merely "acting".

"It troubles me greatly to hear that people see me as an expert or an authority…

"I suppose it’s also an issue of personal style. To me, writing without a strong voice, writing filled with second guessing and disclaimers, is tedious and difficult to slog through. I go out of my way to write in a strong voice because it’s more effective. But whenever I post in a strong voice, it is also an implied invitation to a discussion, a discussion where I often change my opinion and invariably learn a great deal about the topic at hand. I believe in the principle of strong opinions, weakly held…"

To sum up, Atwood isn’t a real authority, but he plays one on the Internet.

Here’s the flip side to all of this. Liberty, Hanselman, Atwood, Fowler, et. al. have made great contributions to software programming. They write good stuff, not only in the sense of being entertaining, but also in the sense that they shape the software development "community" and how software developers — from architects down to lowly code monkeys — think about coding and think about the correct way to code. In any other profession, this is the very definition of "authority".

In literary theory, this is known as authorial angst. It occurs when an author doesn’t believe in his own project. He does what he can, and throws it out to the world. If his work achieves success, he is glad for it, but takes it as a chance windfall, rather than any sort of validation of his own talents. Ultimately, success is a bit perplexing, since there are so many better authors who never achieved success in their own times, like Celine or Melville.

One of my favorite examples of this occurs early in Jean-Francois Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition in which he writes that he knows the book will be very successful, if only because of the title and his reputation, but … The most famous declaration of authorial angst is found in Mark Twain’s notice inserted into The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn:

"Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot."

In Jeff Atwood’s case, the authority angst seems to take the following form: Jeff may talk like an authority, and you may take him for an authority, but he does not consider himself one. If treating him like an authority helps you, then that’s all well and good. And if it raises money for him, then that’s all well and good, too. But don’t use his perceived authority as a way to impugn his character or to discredit him. He never claimed to be one. Other people are doing that.

[The French existentialists are responsible for translating Heidegger’s term angst as ennui, by the way, which has a rather different connotation (N is for Neville who died of ennui). In a French translation class I took in college, we were obliged to try to translate ennui, which I did rather imprecisely as "boredom". A fellow student translated it as "angst", for which the seminar tutor accused her of tossing the task of translation over the Maginot line. We finally determined that the term is untranslatable. Good times.]

The problem these authorities have with authority may be due to the fact that authority is a role. In Alasdaire MacIntyre’s After Virtue, a powerful critique of what he considers to be the predominant ethical philosophy of modern times, Emotivism, MacIntyre argues that the main characteristics (in Shaftesbury’s sense) of modernity are the Aesthete, the Manager and the Therapist. The aesthete replaces morals as an end with a love of patterns as an end. The manager eschews morals for competence. The therapist overcomes morals by validating our choices, whatever they may be. These characters are made possible by the notion of expertise, which MacIntyre claims is a relatively modern invention.

"Private corporations similarly justify their activities by referring to their possession of similar resources of competence. Expertise becomes a commodity for which rival state agencies and rival private corporations compete. Civil servants and managers alike justify themselves and their claims to authority, power and money by invoking their own competence as scientific managers of social change. Thus there emerges an ideology which finds its classical form of expression in a pre-existing sociological theory, Weber’s theory of bureaucracy."

To become an authority, one must begin behaving like an authority. Some tech authors such as Jeffrey Richter and Juval Lowy actually do this very well. But sacrifices have to be made in order to be an authority, and it may be that this is what the anti-authoritarians of the tech world are rebelling against. When one becomes an authority, one must begin to behave differently. One is expected to have a certain realm of competence, and when one acts authoritatively, one imparts this sense of confidence to others: to developers, as well as the managers who must oversee developers and justify their activities to upper management.

Upper management is already always a bit suspicious of the software craft. They tolerate certain behaviors in their IT staff based on the assumption that they can get things done, and every time a software project fails, they justifiably feel like they are being hoodwinked. How would they feel about this trust relationship if they found out that one of the figures their developers are holding up as an authority figure is writing this:

"None of us (in software) really knows what we’re doing. Buildings have been built for thousands of years and software has been an art/science for um, significantly less (yes, math has been around longer, but you know.) We just know what’s worked for us in the past."

This resistance to putting on the role of authority is understandable. Once one puts on the hoary robes required of an authority figure, one can no longer be oneself anymore, or at least not the self one was before. Patrick O’Brien describes this emotion perfectly as he has Jack Aubrey take command of his first ship in Master and Commander.

"As he rowed back to the shore, pulled by his own boat’s crew in white duck and straw hats with Sophie embroidered on the ribbon, a solemn midshipman silent beside him in the sternsheets, he realized the nature of this feeling. He was no longer one of ‘us’: he was ‘they’. Indeed, he was the immediately-present incarnation of ‘them’. In his tour of the brig he had been surrounded with deference — a respect different in kind from that accorded to a lieutenant, different in kind from that accorded to a fellow human being: it had surrounded him like a glass bell, quite shutting him off from the ship’s company; and on his leaving the Sophie had let out a quiet sigh of relief, the sigh he knew so well: ‘Jehovah is no longer with us.’

"It is the price that has to be paid,’ he reflected."

It is the price to be paid not only in the Royal Navy during the age of wood and canvas, but also in established modern professions such as architecture and medicine. All doctors wince at recalling the first time they were called "doctor" while they interned. They do not feel they have the right to wear the title, much less be consulted over a patient’s welfare. They feel intensely that this is a bit of a sham, and the feeling never completely leaves them. Throughout their careers, they are asked to make judgments that affect the health, and often even the lives, of their patients — all the time knowing that their’s is a human profession, and that mistakes get made. Every doctor bears the burden of eventually killing a patient due to a bad diagnosis or a bad prescription or simply through lack of judgment. Yet bear it they must, because gaining the confidence of the patient is also essential to the patient’s welfare, and the world would likely be a sorrier place if people didn’t trust doctors.

So here’s one possible analysis: the authorities of the software engineering profession need to man up and simply be authorities. Of course there is bad faith involved in doing so. Of course there will be criticism that they frauds. Of course they will be obliged to give up some of the ways they relate to fellow developers once they do so. This is true in every profession. At the same time every profession needs its authorities. Authority holds a profession together, and it is what distinguishes a profession from mere labor. The gravitational center of any profession is the notion that there are ways things are done, and there are people who know what those ways are. Without this perception, any profession will fall apart, and we will indeed be merely playaz taking advantage of middle management and making promises we cannot fulfill. Expertise, ironically, explains and justifies our failures, because we are able to interpret failure as a lack of this expertise. We then drive ourselves to be better. Without the perception that there are authorities out there, muddling and mediocrity become the norm, and we begin to believe that not only can we not do better, but we aren’t even expected to.

This is a traditionalist analysis. I have another possibility, however, which can only be confirmed through the passage of time. Perhaps the anti-authoritarian impulse of these crypto-authorities is a revolutionary legacy of the soixantes-huitards. From Guy Sorman’s essay about May ’68, whose fortieth anniversary passed unnoticed:

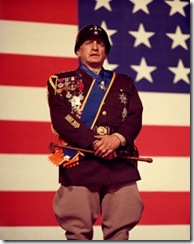

"What did it mean to be 20 in May ’68? First and foremost, it meant rejecting all forms of authority—teachers, parents, bosses, those who governed, the older generation. Apart from a few personal targets—General Charles de Gaulle and the pope—we directed our recriminations against the abstract principle of authority and those who legitimized it. Political parties, the state (personified by the grandfatherly figure of de Gaulle), the army, the unions, the church, the university: all were put in the dock."

Just because things have been done one way in the past doesn’t mean this is the only way. Just because authority and professionalism are intertwined in every other profession, and perhaps can longer be unraveled at this point, doesn’t mean we can’t try to do things differently in a young profession like software engineering. Is it possible to build a profession around a sense of community, rather than the restraint of authority?

I once read a book of anecdotes about the 60’s, one of which recounts a dispute between two groups of people in the inner city. The argument is about to come to blows when someone suggests calling the police. This sobers everyone up, and with cries of "No pigs, no pigs" the disputants resolve their differences amicably. The spirit that inspired this scene, this spirit of authority as anti-pattern, is no longer so ubiquitous, and one cannot really imagine civil disputes being resolved in such a way anymore. Still, the notion of a community without authority figures is a seductive one, and it may even be doable within a well-educated community such as the web-based world of software developers. Perhaps it is worth trying. The only thing that concerns me is how we are to maintain the confidence of management as we run our social experiment.