Tonight the final season of Battlestar Galactica commences. Whereas the original 80’s science fiction series was based on Biblical themes, perhaps even Mormon themes, the re-imagining of the series in the 00’s uses pagan mythology as a backdrop, along with references to straight-from-the-headlines contemporary politics as well as a post-modern self-referentially — due not least to the fact that it is a remake of a popular series.

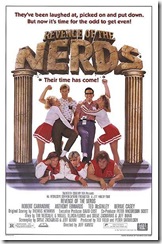

There is a fantastic quality to childhood that cannot be recaptured, and probably one should not make the attempt. The Big Mac, I have found as an adult, does not taste as good as it did to my ten year old self. It is almost inedible. It also seems smaller. Going back to see the original Star Wars is an exercise in nostalgia, but along with it is the sense that those movies weren’t really that good after all. The Catcher In The Rye is a similar disappointment, and the brilliant insights I once thought I gleaned from it are now embarrassing to recall. (But the literary journey with Holden Caulfield had seemed so deep at the time.)

Which brings us to the original Battlestar Galactica, which I caught a glimpse of a few months ago on the SciFi Channel, and found to be virtually unwatchable.

Giambattista Vico, the 18th century philologist, used this unsatisfactory experience of reviewing the past as his starting point for his interpretation of history. The prior centuries had been dominated by notions of an Ancient Wisdom which the Renaissance was supposed to be recovering, or re-birthing (re-naissance). This included, of course, the rediscovery of Plato in the original Greek, of course, preserved by Islamic scholars and philosophers when Europe was suffering through its Dark Age. It was also intended to include, however, works purported to be written by ancient Egyptian wise men known as The Corpus Hermeticum.

Vico had a particular take on all of this. He divides the history of various cultures into three distinct phases: the age of gods, the age of heroes, and the age of men. These three phases mirror the three phases of human development: childhood, adolescence, and maturity.

A child, as any parent can tell you, finds endless entertainment in a cardboard box, and will play with that in lieu of the fantastic educational toys you bought for their birthdays, and which came in said cardboard box. The adult, seeking to capture this childhood experience will try to magnify the significance of the box in order to make it seem as worthy of his adult attention, and in order to justify his youthful affection for cardboard. If you read any psychoanalytic works from the 60’s and 70’s, you’ll discover that this is a recurring theme.

For Vico, a similar thing occurs when we look at history. Because we read ancient writings and find people who worship, say, stone circles, we sometimes jump to the conclusion that there was — and still is – something remarkable about those circles. The mistake comes from thinking that our younger selves see the world the same way we do today.

This makes it seem as if Vico is merely a historicist, or the sort of historical colonialist who tends to look down on the past. This is far from the case. For Vico, each advancement in culture comes at a price. With cultural maturity comes a loss of vitality and a certain amount of cynicism. While in the modern world we might speak of freedom and the rights of man, we fail to think of them with the frank sincerity of our ancestors. And the ability to treat these ideal notions as if they were real is something enviable, but difficult to achieve for the modern (much less the post-modern). How does one go back to one’s youth?

Did I say above that Vico divides history into three phases? I misspoke. He actually divides it into six phases, for the three cultural phases occur once, and then recur. The first series he calls the corso, while the second he calls the ricorso. The same things, in a sense, occur in both the corso and the ricorso. In each, there is an age of gods, then an age of heroes, then an age of men. What distinguishes them is that while in the first series everything happens newly, in the second we can achieve some sort of awareness of what is happening to us, because it has all happened before. Whether this serves us in a way that allows us to shape the unfolding of the ricorso, following Santayana’s dictum, is hard to say. Probably not.

But it does give us a special appreciation for what is going on, in the least. The modern can draw parallels between the current age of men and the last age of men that came with the slow dissolution of the Roman Empire. He can find signs of more vital cultures that parallel that of the German tribes, say, who were still in the age of heroes after Rome had long abandoned it, and try to find similar circumstances today that can slow the cultural dissolution that a cynical society portends. Or perhaps not. Perhaps all that Vico provides us is a tragic framework in which to view cultural history, since the essential power of all tragedies, whether it is that of Oedipus or that of Willy Loman, is that the audience always knows how the play will end.

For those who have not been watching Battlestar Galactica, the new series, now in its fourth season, is about humans in a far off star system — it is unclear whether they are from our future or from our past — who are almost entirely annihilated by a race of robots called Cylons. Out of the billions of people who once lived in this system, only some forty thousand survive. They are on a blind mission across the universe, attempting to escape the Cylons who are still trying to eradicate them. They try to keep up their spirits through their faith though, unlike in the original series, and more like the world in which the audience for Battlestar Galactica lives, their faith waxes and wanes, sometimes bolstered by adversity but more often destroyed by it. The central tenet of their peculiar religion is a variation on Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence, "All of this has happened before, all of this will happen again," which they repeat to themselves throughout the series. In order to preserve good order in the face of a hopeless situation, the last leaders of the human race, in an act of bad faith, tell their followers that they are headed toward an ancient planet known, in their mythologies, as Earth.