Interviewing has been on a my mind, of late, as my company is in the middle of doing quite a bit of hiring. Technical interviews for software developers are typically an odd affair, performed by technicians who aren’t quite sure of what they are doing upon unsuspecting job candidates who aren’t quite sure of what they are in for.

Part of the difficulty is the gap between hiring managers, who are cognizant of the fact that they are not in position to evaluate the skills of a given candidate, and the in-house developers, who are unsure of what they are supposed to be looking for. Is the goal of a technical interview to verify that the interviewee has the skills she claims to possess on her resume? Is it to rate the candidate against some ideal notion of what a software developer ought to be? Is it to connect with a developer on a personal level, thus assuring through a brief encounter that the candidate is someone one will want to work with for the next several years? Or is it merely to pass the time, in the middle of more pressing work, in order to have a little sport and give job candidates a hard time?

It would, of course, help if the hiring manager were able to give detailed information about the kind of job that is being filled, the job level, perhaps the pay range — but more often than not, all he has to work with is an authorization to hire “a developer”, and he has been tasked with finding the best that can be got within limiting financial constraints. So again, the onus is upon the developer-cum-interviewer to determine his own goals for this hiring adventure.

Imagine yourself as the technician who has suddenly been handed a copy of a resume and told that there is a candidate waiting in the meeting room. As you approach the door of the meeting room, hanging slightly ajar, you consider what you will ask of him. You gain a few more minutes to think this over as you shake hands with the candidate, exchange pleasantries, apologize for not having had time to review his resume and look blankly down at the sheet of buzzwords and dates on the table before you.

Had you more time to prepare in advance, you might have gone to sites such as Ayenda’s blog, or techinterviews.com, and picked up some good questions to ask. On the other hand, the value of these questions is debatable, as it may not be clear that these questions are necessarily a good indicator that the interviewee had actually been doing anything at his last job. He may have been spending his time browsing these very same sites and preparing his answers by rote. It is also not clear that understanding these high-level concepts will necessarily make the interviewee good in the role he will eventually be placed in, if hired.

Is understanding how to compile a .NET application with a command line tool necessarily useful in every (or any) real world business development task? Does knowing how to talk about the observer pattern make him a good candidate for work that does not really involve developing monumental code libraries? On the other hand, such questions are perhaps a good gauge of the candidate’s level of preparation for the interview, and can be as useful as checking the candidate’s shoes for a good shine to determine how serious he is about the job and what level of commitment he has put into getting ready for it. And someone who prepares well for an interview will, arguably, also prepare well for his daily job.

You might also have gone to Joel Spolsky’s blog and read The Guerrilla Guide To Interviewing in order to discover that what you are looking for is someone who is smart and gets things done. Which, come to think of it, is especially helpful if you are looking for superstar developers and have the money to pay them whatever they want. With such a standard, you can easily distinguish between the people who make the cut and all the other maybe candidates. On the other hand, in the real world, this may not be an option, and your objective may simply be to distinguish between the better maybe candidates and the less-good maybe candidates. This task is made all the harder since you are interviewing someone who is already a bit nervous and, maybe, has not even been told, yet, what he will be doing in the job (look through computerjobs.com sometime to see how remarkably vague most job descriptions are) for which he is interviewing.

There are many guidelines available online giving advice on how to identify brilliant developers (but is this really such a difficult task?) What there is a dearth of is information on how to identify merely good developers — the kind that the rest of us work with on a daily basis and may even be ourselves. Since this is the real purpose of 99.9% of all technical interviews, to find a merely good candidate, following online advice about how to find great candidates may not be particularly useful, and in fact may even be counter-productive, inspiring a sense of inferiority and persecution in a job candidate that is really undeserved and probably unfair.

Perhaps a better guideline for finding candidates can be found not in how we ought to conduct interviews in an ideal world (with unlimited budgets and unlimited expectations), but in how technical interviews are actually conducted in the real world. Having done my share of interviewing, watching others interview, and occasionally being interviewed myself, it seems to me that in the wild, technical interviews can be broken down into three distinct categories.

Let me, then, impart my experience, so that you may find the interview technique most appropriate to your needs, if you are on that particular side of the table, or, conversely, so that you may better envision what you are in for, should you happen to be on the other side of the table. There are three typical styles of technical interviewing which I like to call: 1) Jump Through My Hoops, 2) Guess What I’m Thinking, and 3) Knock This Chip Off My Shoulder.

Jump Through My Hoops

Jump Through My Hoops is, of course, a technique popularized by Microsoft and later adopted by companies such as Google. In its classical form, it requires an interviewer to throw his Birkenstock shod feet over the interview table and fire away with questions that have nothing remotely to do with programming. Here are a few examples from the archives. The questions often involve such mundane objects as manhole covers, toothbrushes and car transmissions, but you should feel free to add to this bestiary more philosophical archetypes such as married bachelors, morning stars and evening stars, Cicero and Tully, the author of Waverly, and other priceless gems of the analytic school. The objective, of course, is not to hire a good car mechanic or sanitation worker, but rather to hire someone with the innate skills to be a good car mechanic or sanitation worker should his IT role ever require it.

Over the years, technical interviewers have expanded on the JTMH with tasks such as writing out classes with pencil and paper, answering technical trivia, designing relational databases on a whiteboard, and plotting out a UML diagram with crayons. In general, the more accessories required to complete this type of interview, the better.

Some variations of JTMH rise to the level of Jump Through My Fiery Hoops. One version I was involved with required calling the candidate the day before the job interview and telling him to write a complete software application to specification, which would then be picked apart by a team of architects at the interview itself. It was a bit of overkill for an entry-level position, but we learned what we needed to out of it. The most famous JTMFH is what Joel Spolsky calls The Impossible Question, which entails asking a question with no correct answer, and requires the interviewer to frown and shake his head whenever the candidate makes any attempt to answer the question. This particular test is also sometimes called the Kobayashi Maru, and is purportedly a good indicator of how a candidate will perform under pressure.

Guess What I’m Thinking

Guess What I’m Thinking, or GWIT, is a more open ended interview technique. It is often adopted by interviewers who find JTMH a bit too constricting. The goal in GWIT is to get through an interview with the minimum amount of preparation possible. It often takes the form, “I’m working on such-and-such a project and have run into such-and-such a problem. How would you solve it?” The technique is most effective when the job candidate is given very little information about either the purpose of the project or the nature of the problem. This establishes for the interviewer a clear standard for a successful interview: if the candidate can solve in a few minutes a problem that the interviewer has been working on for weeks, then she obviously deserves the job.

A variation of GWIT which I have participated in requires showing a candidate a long printout and asking her, “What’s wrong with this code?” The trick is to give the candidate the impression that there are many right answers to this question, when in fact there is only one, the one the interviewer is thinking of. As the candidate attempts to triangulate on the problem with hopeful answers such as “This code won’t compile,” “There is a bracket missing here,” “There are no code comments,” and “Is there a page missing?” the interviewer can sagely reply “No, that’s not what I’m looking for,” “That’s not what I’m thinking of, “That’s not what I’m thinking of, either,” “Now you’re really cold” and so on.

This particular test is purportedly a good indicator of how a candidate will perform under pressure.

Knock This Chip Off My Shoulder

KTCOMS is an interviewing style often adopted by interviewers who not only lack the time and desire to prepare for the interview, but do not in fact have any time for the interview itself. As the job candidate, you start off in a position of wasting the interviewer’s time, and must improve his opinion of you from there.

The interviewer is usually under a lot of pressure when he enters the interview room. He has been working 80 hours a week to meet an impossible deadline his manager has set for him. He is emotionally in a state of both intense technical competence over a narrow area, due to his life-less existence for the past few months, as well as great insecurity, as he has not been able to satisfy his management’s demands.

While this interview technique superficially resembles JTMFH, it is actually quite distinct in that, while JTMFH seeks to match the candidate to abstract notions about what a developer ought to know, KTCOMS is grounded in what the interviewer already knows. His interview style is, consequently, nothing less that a Nietzschean struggle for self-affirmation. The interviewee is put in the position of having to prove herself superior to the interviewer or else suffer the consequences.

Should you, as the interviewer, want to prepare for KTCOMS, the best thing to do is to start looking up answers to obscure problems that you have encountered in your recent project, and which no normal developer would ever encounter. These types of questions, along with an attitude that the job candidate should obviously already know the answers, is sure to fluster the interviewee.

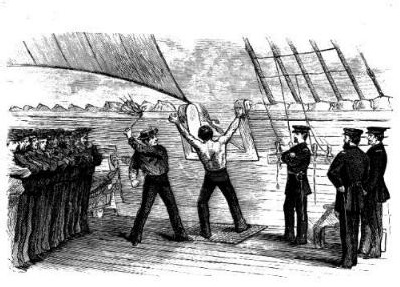

As the interviewee, your only goal is to submit to the superiority of the interviewer. “Lie down” as soon as possible. Should you feel any umbrage, or desire to actually compete with the interviewer on his own turf, you must crush this instinct. Once you have submitted to the interviewer (in the wild, dogs generally accomplish this by lying down on the floor with their necks exposed, and the alpha male accepts the submissive gesture by laying its paw upon the submissive animal) he will do one of two things; either he will accept your acquiescence, or he will continue to savage you mercilessly until someone comes in to pull him away.

This particular test is purportedly a good indicator of how a candidate will perform under pressure.

Conclusion

I hope you have found this survey of common interviewing techniques helpful. While I have presented them as distinct styles of interviewing, this should certainly not discourage you from mixing-and-matching them as needed for your particular interview scenario. The schematism I presented is not intended as prescriptive advice, but merely as a taxonomy of what is already to be found in most IT environments, from which you may draw as you require. You may, in fact, already be practicing some of these techniques without even realizing it.